Virtual Exhibition: Samuel Pepys’s Diary

Pepys began keeping what he called his ‘journal’ in 1660, continuing until 1669. The Diary is recognised as one of the most important resources for studying the period of the Restoration: crammed on each page with Pepys’s wide-ranging observations and commentaries on his professional and personal life, the Diary offers invaluable insights into political, social, naval and economic history. Transcriptions are from R C Latham and W Matthews, the Diary of Samuel Pepys.

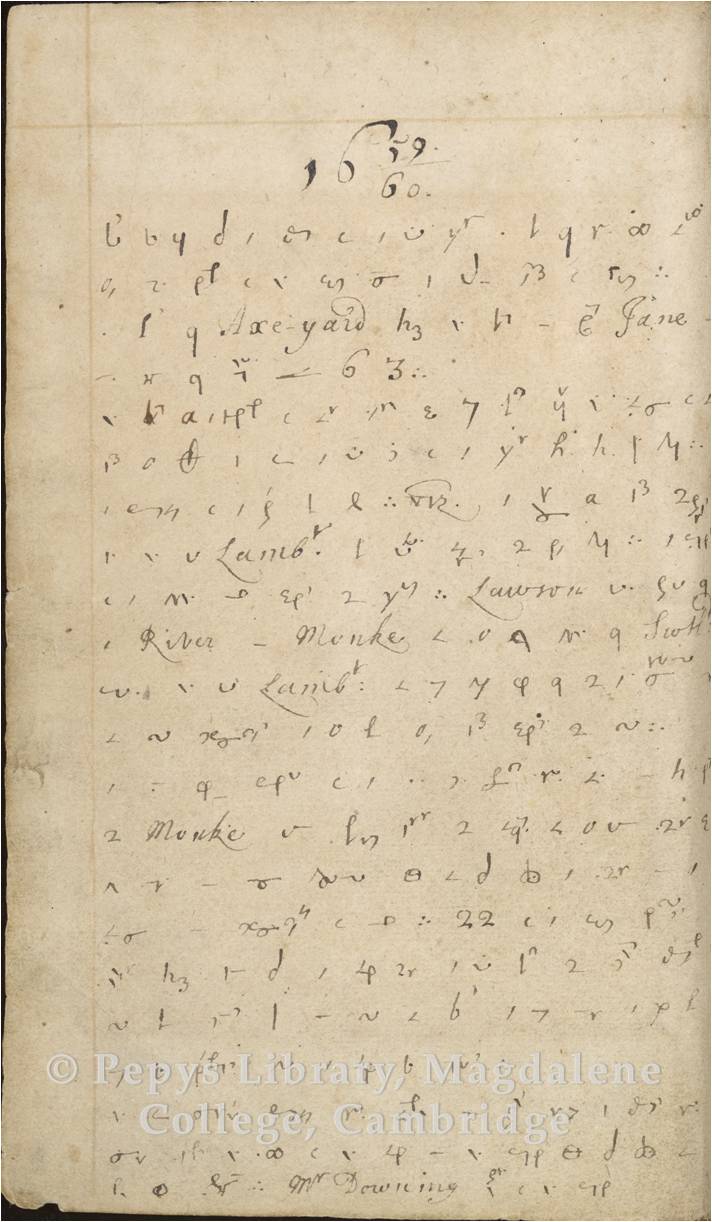

Item 1: Manuscript: The opening of Samuel Pepys’s Diary, 1660

In the introductory passage of the diary, written as the new decade of the 1660s opened, we immediately hit upon important aspects of Pepys’s life and his habits of recording it:

Blessed be God, at the end of the last year I was in very good health, without any sense of my old pain but upon taking of cold.

I lived in Axe=yard [sic], having my wife and servant Jane, and no more in family then us three.

My wife, after the absence of her terms for seven weeks, gave me hopes of her being with child, but on the last day of the year she hath them again.

Pepys sets the scene by describing his personal and family circumstances and we understand that he is conscious of his health, an aspect of life which is very precarious in the 17th century. Pepys ‘old pain’ refers to his bladder and kidney stones, a very large bladder stone having been removed in 1658. So grateful was he to have survived the extremely dangerous and painful operation that he held a special dinner every year on its anniversary.

Pepys and Elizabeth had lived in Axe-Yard, on the west side of Kings Street in Westminster since 1658. Pepys describes both his wife Elizabeth and his servant Jane as part of his ‘family’ – a group of people living in a single household, rather than blood relatives as we would generally use the term today. Pepys’s diary is an important source for our understanding of the development of the English language, and is cited over 1700 times in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Intimate descriptions of Elizabeth Pepys’s ‘terms’, or periods, are recorded several times in the diary. The modern reader, however, would only discover these if they are reading the definitive, unexpurgated edition of the diary by Robert Latham and William Matthews completed in the 1970s. In earlier editions, such descriptions were deemed unsuitable and omitted – as were several other aspects of Pepys’s life such as his extra-marital encounters.

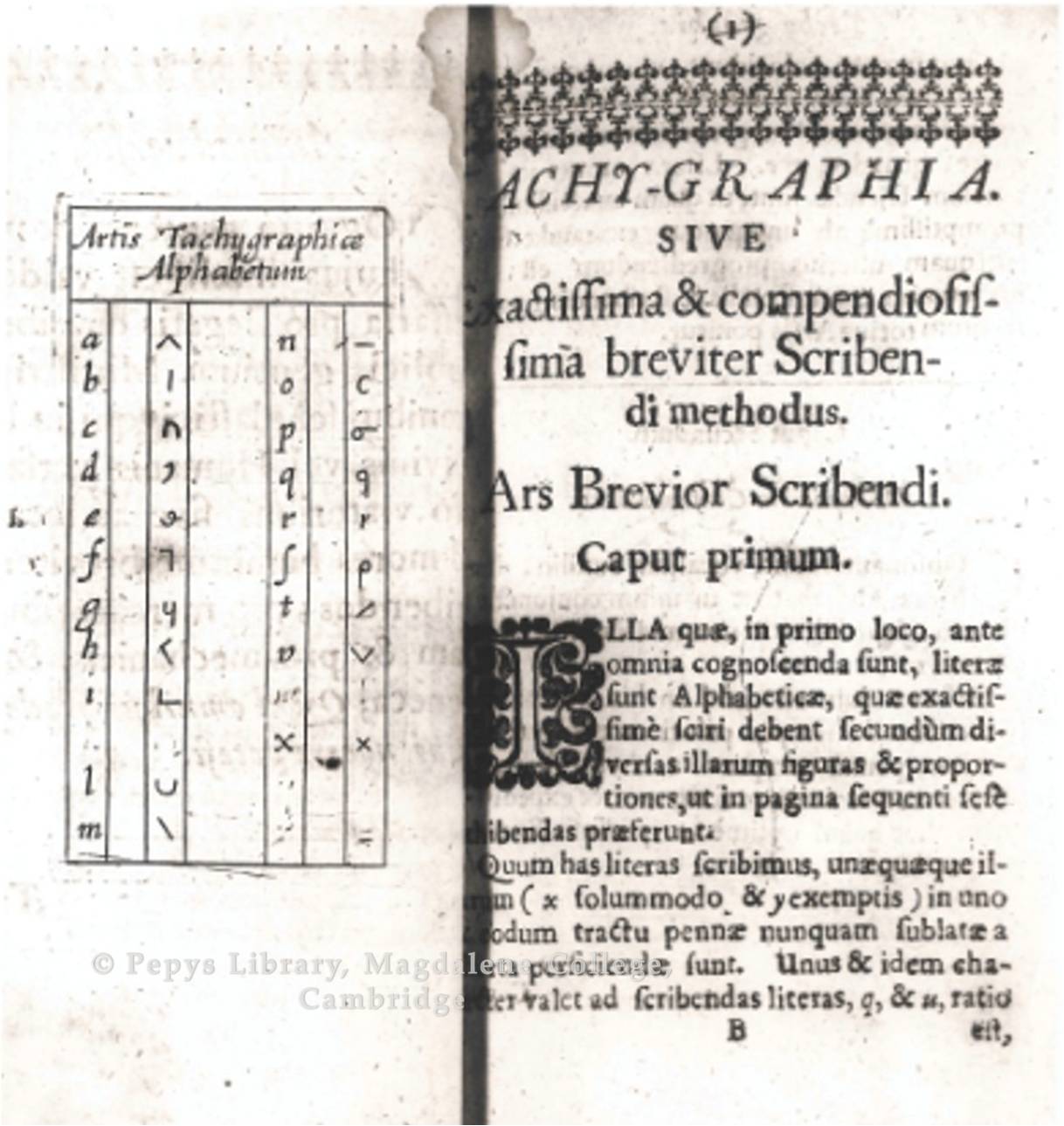

Item 2: Book: A tutor to tachygraphy, by Thomas Shelton

Thomas Shelton, a stenographer of the 17th century, devised one of the most popular shorthand systems of the day. It was Shelton’s tachygraphy or short writing system which Pepys used in his diary, along with his contemporaries Isaac Newton and Henry James, Master of Queens’ College Cambridge. Since Shelton’s shorthand was used in several Cambridge colleges and student clubs, Pepys may well have learnt the system whilst at Magdalene.

By using the shorthand system, Pepys was able to put a great amount of information to paper in a short space of time, and speed was his primary reason for using the system in his diary (although the secrecy aspect may have been an advantage too – his wife Elizabeth would not have had knowledge of the shorthand).

As Pepys’s collection of a wide variety of shorthand manuals and calligraphy copy books attests, Pepys took an interest in handwriting as a discipline and art form in itself. The tutor shown here is one within a collection of such manuals, which Pepys had bound into a single volume. Although popular in its day, Shelton’s shorthand had fallen out of use by the 1770s, making the task of transcribing the Diary all the trickier.

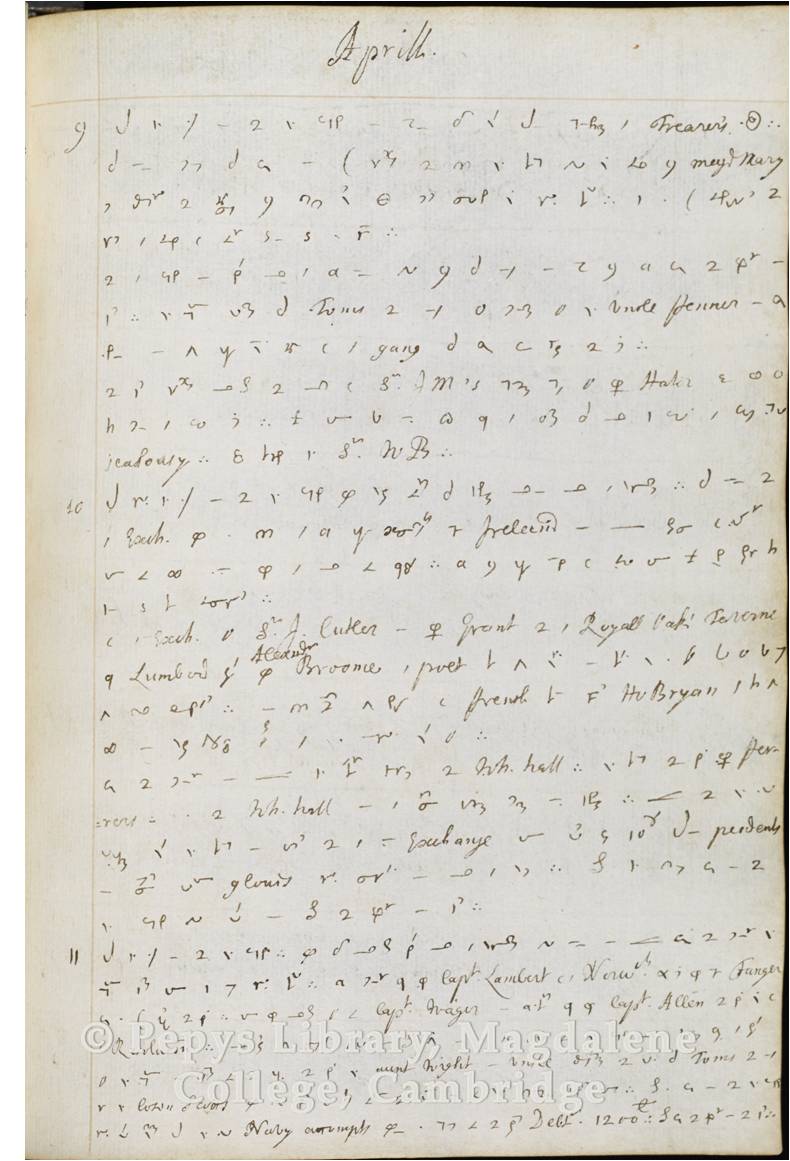

Item 3: Manuscript: Samuel Pepys’s Diary, 10th April 1663

Pepys is significant for documenting an important span of the 17th century, with detailed accounts of the Restoration, the plague of 1665-1666 and the great fire of London. Perhaps as importantly, he records fascinating details about everyday life in the capital during this time. On the 10th April 1663 he writes:

Off the Exchange with Sir J. Cutler and Mr. Grant to the Royall Oake Taverne in Lumbard-street, where Broome the poet was, a merry and witty man I believe, if he be not a little conceited. And here drans a sort of French wine called Ho Bryan, that hath a good and most perticular taste that I never met with.

The wine Pepys is referring to is the distinguished claret Chateau Haut Brion: the name (spelt phonetically as Ho Bryan) is visible about two thirds of the way down the page. This is probably the earliest record of someone drinking a named chateau-bottled wine in the English language. From the diary of Pepys's friend, John Evelyn, we can derive the name of the supplier of this wine:

I had this day much discourse with Monsieur Pontaque, son to the famous & wise Prime President of Bourdeaux: This gent, was owner of that excellent Vignoble of Pontaque Se Obrien, whence the choicest of our Burdeaux-Wines come...

The ‘Prime President of Bourdeaux’ to whom Evelyn refers is Lord Arnaud III de Pontac, who marketed his wine as a luxury product in London, supplying the court of Charles II with Chateau Haut-Brion in 1660, as the King’s wine ledgers demonstrate.

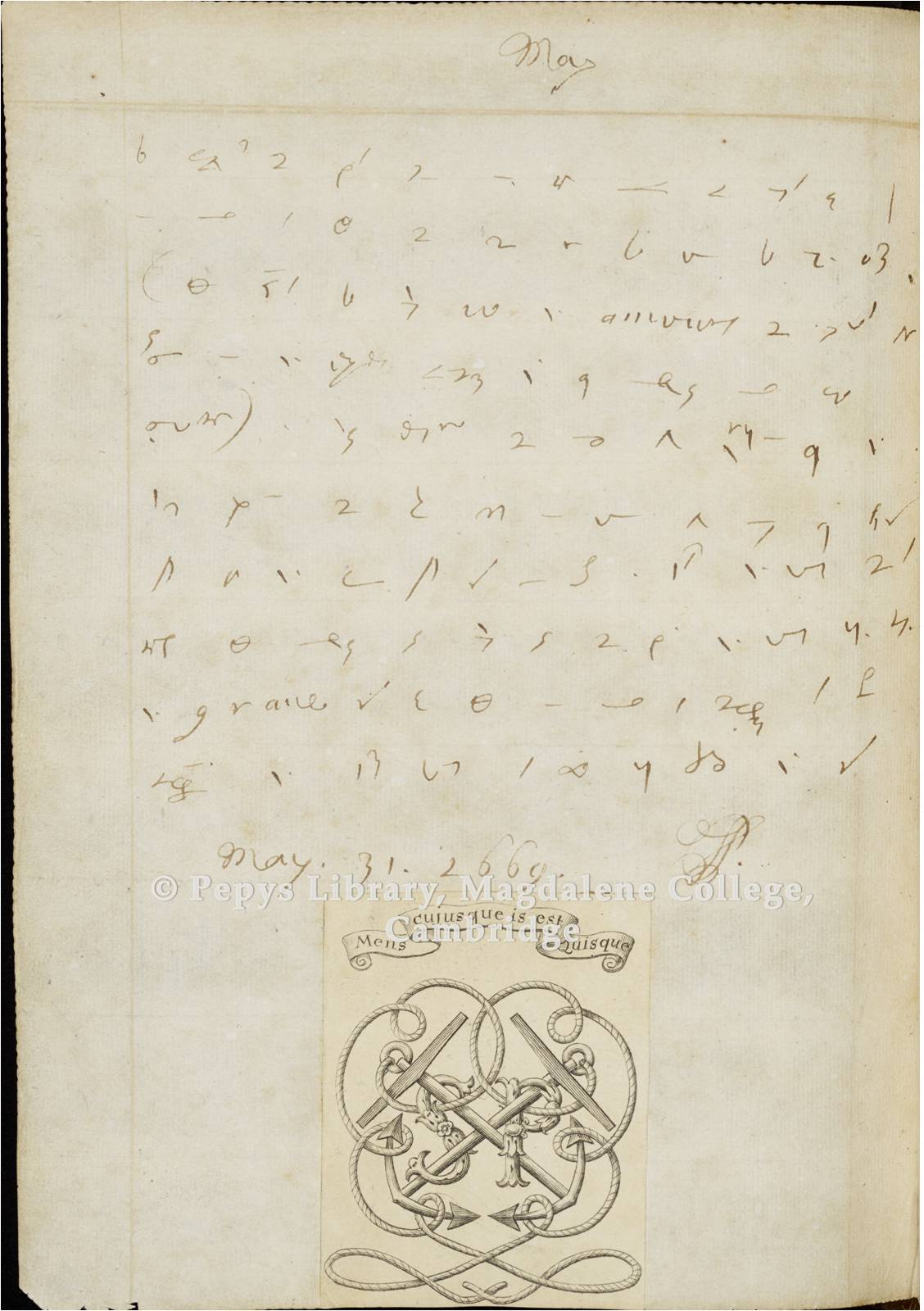

Item 4: Manuscript: The Closing of Samuel Pepys’s Diary, 31st May 1669

Pepys gave up his diary because he thought his eyesight was deteriorating, though his fears of complete blindness turned out to be unfounded. He resolved to keep some notes of his activities with the help of his colleagues, though this never materialised. Pepys did, however, keep a journal documenting his trip to Tangier to help in the dismantling of the English garrison there in 1683. The journal, however, is written in a reportage style which somewhat lacks the vivacity of his earlier work. It is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and has been edited in C S Knighton, Pepys’s Later Diaries.

The final passage of the diary reads:

And thus ends all that I doubt I shall ever be able to do with my own eyes in the keeping of my journall, I being not able to do it any longer, having done now so long as to undo my eyes almost every time that I take a pen in my hand; and, therefore, whatever comes of it, I must forbear: and, therefore resolve from this time forward to have it kept by my people in long-hand, and must therefore be contented to set down no more than is fit for them and all the world to know; or, if there be any thing, which cannot be much, now my amours to Deb are past, and my eyes hindering me in almost all other pleasures, I must endeavour to keep a margin in my book open, to add here and there, a note in short-hand with my own hand.

And so I betake myself to that course, which [is] almost as much as to see myself go into my grave - for which, and all the discomforts that will accompany my being blind, the good God prepare me!

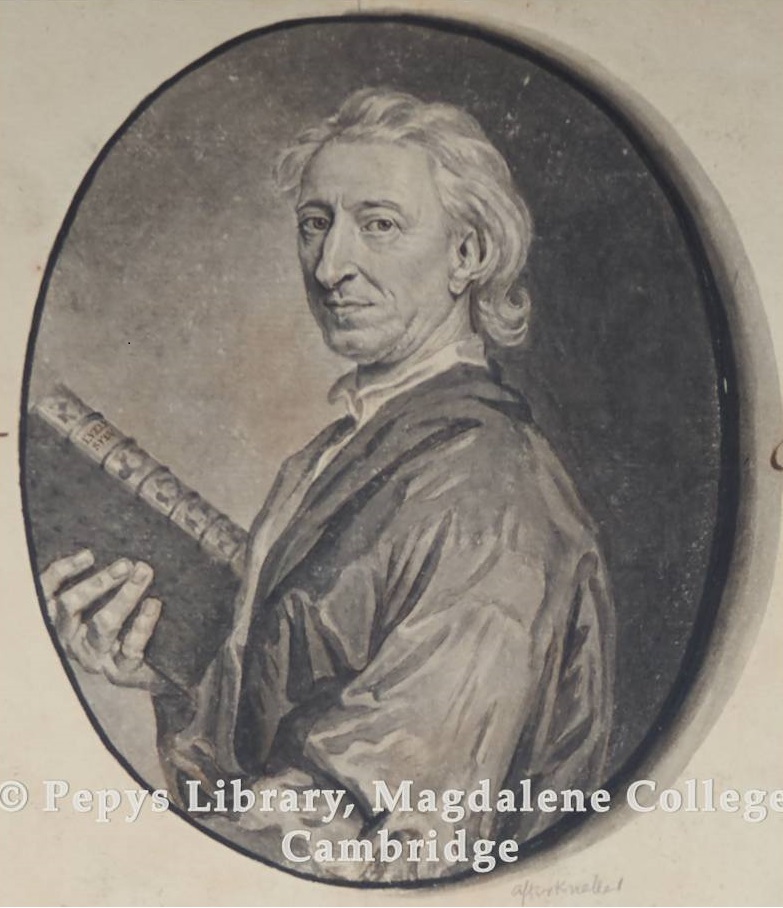

Item 5: Print: Engraving of John Evelyn

In the diary Pepys records the beginning of a lasting friendship with John Evelyn, another great diarist; a friendship represented in this engraving which Pepys arranges alongside those other close companions in his albums of engraved portraits or ‘Heads’. A century and a half later, it was John Evelyn’s diary which was published first and to great acclaim in 1818. This success prompted those at Magdalene who were aware of the existence of Pepys’s diary, which had come to the College as part of the library and remained there virtually unread, to ponder on publication. Lord Grenville, former Prime Minister and uncle to the Master of Magdalene at the time, George Neville-Grenville, commented that the publication of Pepys’s diary would form an ‘excellent accompaniment to Evelyn’s delightful diary’.

Item 6: Portrait of John Smith

John Smith, the first person to transcribe Pepys’s diary out of the shorthand in its preparation for publication, completed a monumental task under challenging circumstances. Lord Grenville, who had viewed the first volume of the diary and had been able to make an attempt at transcribing the opening lines using his knowledge of shorthand formed as a law student, told George Neville-Grenville that ‘Any man of ordinary talent’ would be able to transcribe the diary in ‘a few months’. This was a severe underestimation of the work involved. Smith, a 19-year-old undergraduate student at St John’s College, Cambridge, was eventually appointed to complete the task after George Neville-Grenville and his brother Richard had shown a lack of enthusiasm to undertake the work themselves. Richard, nevertheless, served as the editor of the diary; and in 1825, Richard – now Lord Braybrooke – published under his own name. Braybrooke never met Smith to discuss the work, and upon receiving the transcription, he proceeded to make a somewhat clumsy job of editing and analysing the text. Braybrooke was fortunate, however, that Smith had made a good transcription of Pepys’s shorthand and that the content of the diary was so rich: it was published to great admiration.

Smith’s methods of working were never explained in Braybrooke’s introduction to the diary. the young scholar only received a passing acknowledgement for what turned out to be a task which took him three years and for which he was paid 200 pounds. Despite Smith approaching shorthand experts of the time, he was never told, nor did he find out for himself until he was some way through the transcription, that Pepys used a standard form of shorthand. It was only after much effort at deciphering from first principles, that Smith the came up the ‘Tachygraphy’ displayed above. In 1858, he wrote a letter to the Illustrated London News in a ‘tell all’ account of his work, writing that he worked on the transcription for between twelve and fourteen hours a day: ‘much of it was in minute characters, greatly faded, and inscribed on almost transparent paper – very trying and injurious indeed to the visual organs’. This portrait hangs in the Pepys Library, where library staff regularly tell visitors of John Smith’s vital work, which brought the diary to the public’s attention.